Babiščina / Heirloom

(2019–2024)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sometime in the 1960s, Marija Kobale (Mica for short) decided to visit the dentist in a nearby town and encase a damaged tooth in a golden veneer. Today, she couldn't say exactly what was wrong with the tooth, where the dentist was based, which year specifically this occurred in, or how much it cost – but what’s certain is that the tooth remained with her until 2013, when it was removed and replaced by an artificial set. Sixty years later, Mica gave the tooth to her granddaughter, thinking she might melt it down and use the gold for something useful. What she couldn’t have predicted was that her granddaughter, Lucija Rosc, would take the tooth in question, turn it into a gold coating for her own dying tooth, and film the process.

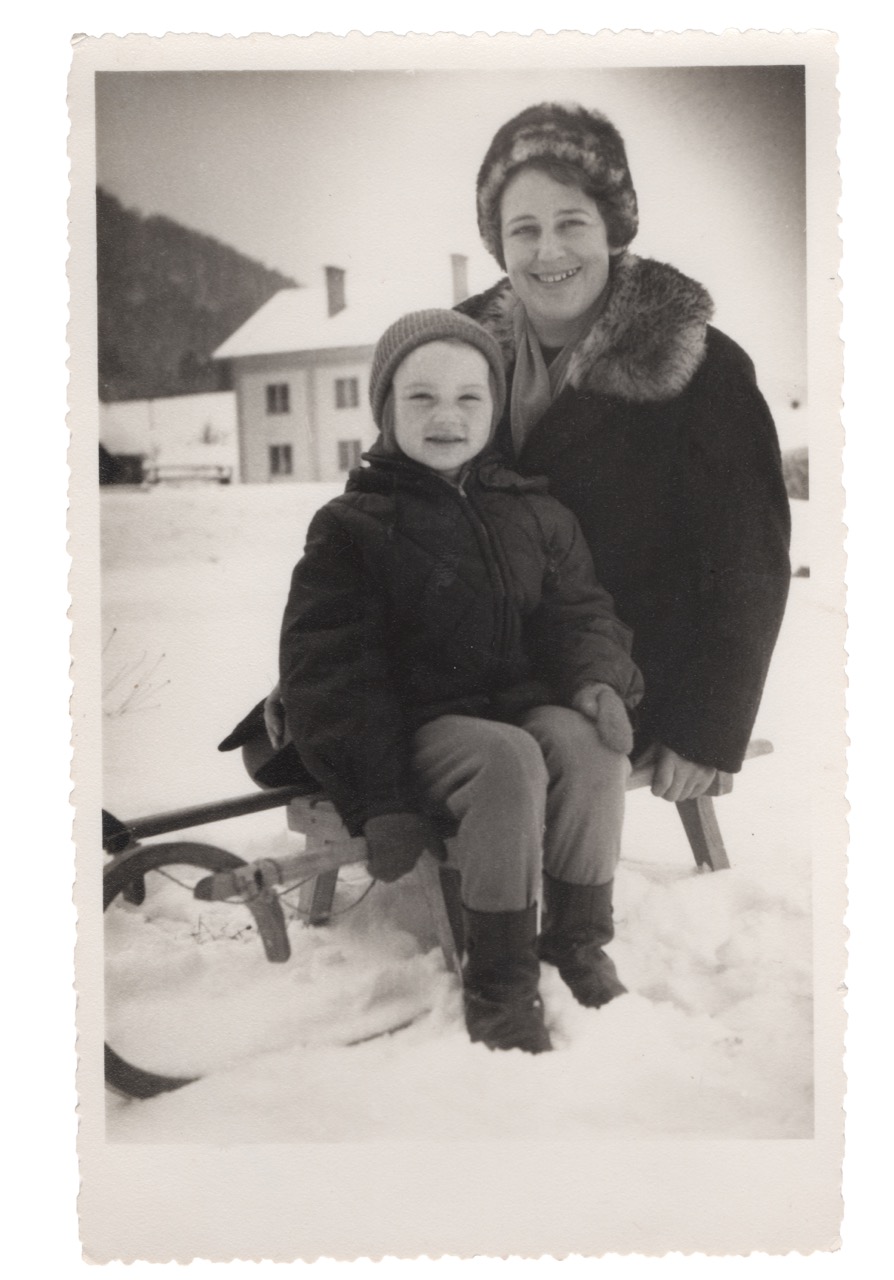

The tooth began its journey as a fashionable accessory, coolness solidified in the general atmosphere of 1960s Yugoslavia. And Mica would certainly fit the vibe – one of the archival photographs that Lucija used in the past shows a young Mica on a motorcycle, smiling broadly at someone we cannot see. It’s not difficult to imagine her character, especially if we’re familiar with Lucija’s work. In her project Mica Reads Jokes (2023), the photographer produced a vinyl record of her grandmother’s collection of jokes, some of them quite raunchy – and made funnier by the fact that it’s Mica’s voice reading them for us. She used to keep a little notebook to collect the jokes and write down her favourites, pulling it out during a quiet moment at family gatherings and testing the jokes on her relatives.

Lucija, who dedicated several exhibitions (Superpositions, Škuc gallery, 2022; Podmet, Miklova hiša gallery, 2023) to her relationship with her grandparents, has now chosen to continue exploring the topic and dedicate a project solely to her grandmother. The artist is once again dealing with topics of family dynamics and memory, and still uses photography as her preferred medium. But the real focus of the exhibition is a performative documentary film about the tooth’s journey from Mica to Lucija; its transfer is a gesture of passing down an heirloom, and the tooth becomes a totem of sorts. After all, Lucija used the gold to cure her own dying tooth (fifth bottom left) in a symbolic gesture of succession.

The film oscillates between archival footage of Lucija’s childhood, iPhone-filmed excerpts of her conversations with Mica dated from 2016 to today, and the process of her tooth replacement. We see Mica lost in thought, lovingly forcing her granddaughter to take home food, cutting pictures out of crossword puzzles, and aimlessly tidying up the apartment. There is a scene of Mica looking for her missing slipper, engaging everyone present in the hunt. These scenes show us how Mica is seen by her granddaughter, but they also possess a certain universality, almost as if we were rewatching our own memories. The footage also speaks of Lucija’s artistic practice, which is based on the fictionalisation of personal memory, on collecting, archiving and reinterpreting, but always managing to imbue her narratives with a sense of humour and induced nostalgia.

In this spirit, archival photographs, casts of Lucija’s teeth and Mica’s gold tooth, and documentation of the dental work are all part of the story, where mundane objects are turned into important pieces of the puzzle, presented as almost sacred objects. The project is both playful and vulnerable, with the artist letting us in on the otherwise private and intimate part of her life. The tooth serves as a metaphor for remembrance, with the artist asking whether it is possible to solidify a cherished memory, to make it tangible and concrete, by literally implanting it in one’s body. The project is definitely a homage to her grandmother and a celebration of her character, yet on a more sombre note, it also deals with the fear of losing a loved one and the question of what will remain once they are gone – and how one can carry their legacy into the future.

Hana Čeferin

Sometime in the 1960s, Marija Kobale (Mica for short) decided to visit the dentist in a nearby town and encase a damaged tooth in a golden veneer. Today, she couldn't say exactly what was wrong with the tooth, where the dentist was based, which year specifically this occurred in, or how much it cost – but what’s certain is that the tooth remained with her until 2013, when it was removed and replaced by an artificial set. Sixty years later, Mica gave the tooth to her granddaughter, thinking she might melt it down and use the gold for something useful. What she couldn’t have predicted was that her granddaughter, Lucija Rosc, would take the tooth in question, turn it into a gold coating for her own dying tooth, and film the process.

The tooth began its journey as a fashionable accessory, coolness solidified in the general atmosphere of 1960s Yugoslavia. And Mica would certainly fit the vibe – one of the archival photographs that Lucija used in the past shows a young Mica on a motorcycle, smiling broadly at someone we cannot see. It’s not difficult to imagine her character, especially if we’re familiar with Lucija’s work. In her project Mica Reads Jokes (2023), the photographer produced a vinyl record of her grandmother’s collection of jokes, some of them quite raunchy – and made funnier by the fact that it’s Mica’s voice reading them for us. She used to keep a little notebook to collect the jokes and write down her favourites, pulling it out during a quiet moment at family gatherings and testing the jokes on her relatives.

Lucija, who dedicated several exhibitions (Superpositions, Škuc gallery, 2022; Podmet, Miklova hiša gallery, 2023) to her relationship with her grandparents, has now chosen to continue exploring the topic and dedicate a project solely to her grandmother. The artist is once again dealing with topics of family dynamics and memory, and still uses photography as her preferred medium. But the real focus of the exhibition is a performative documentary film about the tooth’s journey from Mica to Lucija; its transfer is a gesture of passing down an heirloom, and the tooth becomes a totem of sorts. After all, Lucija used the gold to cure her own dying tooth (fifth bottom left) in a symbolic gesture of succession.

The film oscillates between archival footage of Lucija’s childhood, iPhone-filmed excerpts of her conversations with Mica dated from 2016 to today, and the process of her tooth replacement. We see Mica lost in thought, lovingly forcing her granddaughter to take home food, cutting pictures out of crossword puzzles, and aimlessly tidying up the apartment. There is a scene of Mica looking for her missing slipper, engaging everyone present in the hunt. These scenes show us how Mica is seen by her granddaughter, but they also possess a certain universality, almost as if we were rewatching our own memories. The footage also speaks of Lucija’s artistic practice, which is based on the fictionalisation of personal memory, on collecting, archiving and reinterpreting, but always managing to imbue her narratives with a sense of humour and induced nostalgia.

In this spirit, archival photographs, casts of Lucija’s teeth and Mica’s gold tooth, and documentation of the dental work are all part of the story, where mundane objects are turned into important pieces of the puzzle, presented as almost sacred objects. The project is both playful and vulnerable, with the artist letting us in on the otherwise private and intimate part of her life. The tooth serves as a metaphor for remembrance, with the artist asking whether it is possible to solidify a cherished memory, to make it tangible and concrete, by literally implanting it in one’s body. The project is definitely a homage to her grandmother and a celebration of her character, yet on a more sombre note, it also deals with the fear of losing a loved one and the question of what will remain once they are gone – and how one can carry their legacy into the future.

Hana Čeferin